Jeudi 12 Sable 153

I'm very fond of Blixa Bargeld and EN

"He stood in a black leotard, black rubber pants, black rubber boots. Around his neck hung a thoroughly fucked guitar. His skin cleared to his bones, his skull was an utter disaster, scabbed and hacked. Blixa Bargeld. He was the most beautiful man in the world.", Nick Cave wrote of him. Genevieve McGuckin called him a "beauty queen from another planet". Blixa Bargeld's fashion sense, particularly during the 80s, was just as fascinatingly alien and innovative as his highly experimental music.

As implied in my earlier post on Swans, I have a great interest in extreme, violent music that nonetheless eschews masculinity. Abandoning the original territory of loud, abrasive music in masculine peacocking, bringing it into new, experimental contexts, often leads to incredible innovation. Einstürzende Neubauten are another great example of this, and are perhaps the "most experimental" band I've ever been into, if that's something quantifiable. After having no choice but to sell their drumset, the band started to break down the very concept of a musical instrument: if objects like scraps of metal, drills, or shopping trolleys can obviously make noise too, then what makes them any less "musical instruments" than a drum or guitar? At first, they built a sort of makeshift drumset to replace the one they sold, which was further and further modified until it lost all resemblance to the original and could no longer remotely be called a "drumset" -- rules and conventions were gradually disassembled until they were left with a thoroughly deterritorialised music. Furthermore, when they did use conventional instruments, they had no interest in actually playing them in the conventional way; exploring a new realm of sounds through abnormal techniques such as placing guitars on the floor and playing them with bows or electric razors. The ethos of the band was a total breakdown -- or collapse -- of convention, on every possible level; naturally, this also included deconstruction of gender.

Blixa Bargeld's signature scream is a perfect encapsulation of this. Where harsh vocals in extreme music are conventionally very deep, exaggeratedly masculine, employed to intimidate; Bargeld instead opts for an utterly bizarre technique entirely outside the bounds of such ideas of "masculinity" or "femininity": a jarringly high-pitched, shrill shriek, instead evoking thoughts of "strangled cats" and "dying children" (another brilliant Nick Cave quote). Personally, he reminds me of a boiling kettle!

Despite being a guitarist, Bargeld famously despises the instrument, describing it disparagingly as "phallic... in the gestures as well as in the sound", as an "instrument of machismo". In fact, he specifically picked up guitar because of his hatred for it: in order to discover a way to "play guitar without playing guitar". Indeed, none of rock music's characteristic machismo remains remotely intact in Neubauten's music: its violent chaos is completely genderless.

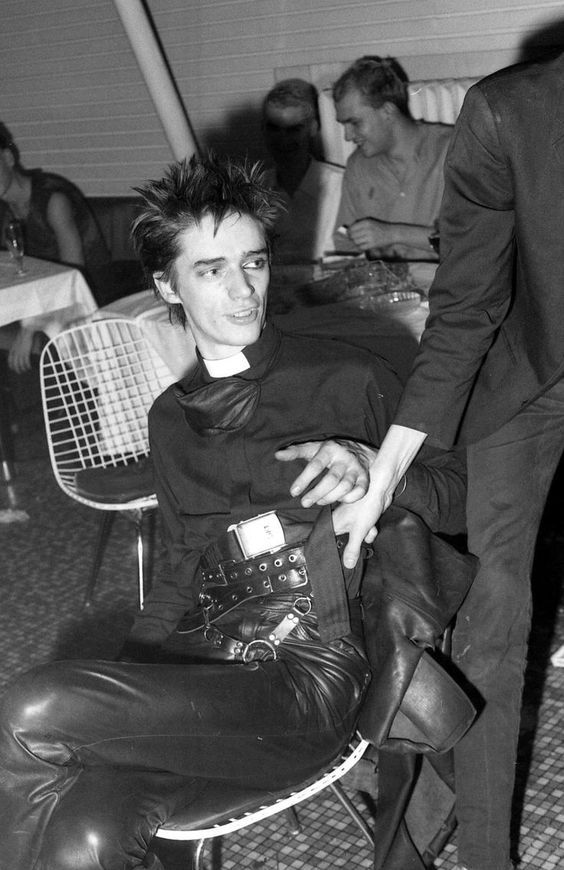

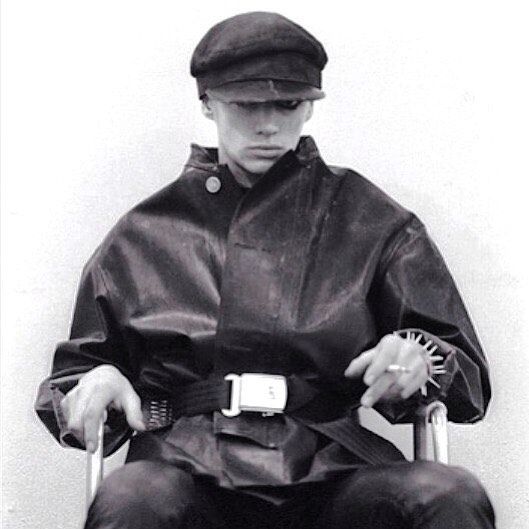

Returning to the subject of Blixa Bargeld's fashion sense, it's the perfect complement to his music. Throwing convention out the window, he would draw from all sorts of sources -- in this photo below, you can see him wearing a clerical collar, a sleeping mask, a seatbelt, and a strapon harness -- tearing them away from their original contexts, and completely repurposing them. In the early 80s, he would also often wear eye makeup on only one eye, which can be read quite directly as an expression of being between masculine and feminine.

You know what, I'll add a couple more photos of him in the 80s, because I really do love his style:

His chosen name, too, reflects his experimental approach: "Blixa" being the name of a felt-tip pen brand, and "Bargeld" meaning "cash" (along with being a reference to dadaist Johannes Theodor Baargeld) -- essentially arbitrary words, given a new context and purpose.

Halber Mensch was their musical peak, in my eyes. The band put themselves forward as a sort of cultural rebirth, in the face of this "gap" in postwar German culture: the feeling that so much of it was irrevocably tainted, the need for something completely new. This gave their music at that time a genuinely post-apocalyptic atmosphere: as if it were created in the ashes of an utterly destroyed world, by the remaining humans trying to re-create music entirely from scratch, having never heard it before. It's simultaneously highly futuristic and forward-thinking, and also highly primal: simplistic, in touch with the most visceral elements of music. The strong focus on rhythm feels tribalistic -- some songs on the album have a sort of call-and-response structure, there's chanting and finger-snapping, it even has a drinking song. But, of course, the band's bizarre deconstruction of musical conventions makes all of these tribalistic, "traditional" elements feel thoroughly alien -- like the tradition of an entirely new culture. The band once referred to their music as "German folk music" -- this could very well have been an ironic joke, but I feel as if there's some substance to it: they're a sort of folk music for a strange, reinvented German culture.

Of course, Blixa Bargeld's style and EN's music have evolved plenty since the period I'm talking about, but that's a topic for another time...

Mercredi 11 Sable 153

Really dislike that hyperindividualist poststructuralist stuff

And now I'm scared that my own thoughts will get mistaken for it*. This whole ideology gets so close to the hitting the mark, but just misses it by a centimetre and then goes flying off into the ether. "Everything is pure illusion and arbitrariness, except consciousness, free will, and the individual, which are totally real and true".

"Consciousness" or the "soul" or the "mind" or the "self" is perhaps the greatest prank ever pulled on us. Why are we still falling for it? The whole invention and popularity of the "philosophical zombie" thought experiment is the perfect demonstration of where people trip up with the so-called "hard problem of consciousness". "When injured, a p-zombie would not feel pain, but would react exactly as an ordinary person would" -- the whole basis of this idea is misguided. People claim not to believe in a soul these days, but when they speak of "consciousness" there's this same phantom doubling going on: this mirror quale of "pain" to the pure physical physiological processes of injury-response. There is no actual logical indication or evidence of these doubles existing -- the "p-zombie" is just another regular human being. "Pain", along with all other "qualia", and furthermore the entire soul/mind/self/consciousness/whatever, is an illusory abstraction.

The hyperindividualist view of poststructuralism -- summarised very crudely, that the individual is prior to everything, the only fixed, cohesive force in a world of arbitrariness -- has, unfortunately, become very popular on the left. You hear these ideas constantly on the topic of gender: that it's all just meaningless social construction, a playground for individual desire and self-determination. However, most people holding such views seem to be very confused about what they actually believe: they love the "gender is a social construct" line, yet also tend to paradoxically believe that gender identity is some innate, fundamental, immutable quality of an individual. They squabble with the right over things like "how many genders there are" -- as if an objective, meaningful answer actually exists, whether that be "only two" or "an endless spectrum" or anything in between. Obviously, what they're actually arguing over is "how many genders should there be", but truly acknowledging the hollowness of gender creates undesirable implications for both sides, as they would like to believe that their own interpretation of gender is some transcendent truth independent of cultural, ideological and historical context.

This cognitive dissonance comes about from the fact that individualist poststructuralism is simply an incoherent position: trying to maintain the individual as a discrete, independent force causes it to fall apart. These people inevitably have to resort to asserting the "truth" of gender identity in order to prop up the "truth" of the individual -- as the "individual" is really just an intersection of many such social forces.

I can't take any ideology seriously that places so much importance on "individual desire", as if individuals were actually independent, autonomous actors. It feels particularly dissonant in the context of current consumer-capitalist society, in which our precious little "desires" and "identities" are very patently manufactured by malicious forces in order to be exploited, on a massive scale.

*Do I have to clarify that I'm not an idealist? The dramatic talk about "reality" is a style I picked up reading/discussing Baudrillard/Debord/etc. I hoped it was obvious by context when I use the words "reality" and "real" whether I mean physical reality or social reality, but I might've been making myself too easy of a target for bad-faith interpretations.

Dimanche 8 Sable 153

Against reality

I could, but I'm not going to go into some whiny self-indulgent rant about how terrible reality is, because it's totally trite at this point. I feel this theme just isn't productive to discuss any further: what I want to talk about here is a constructive, rather than passive, view in the face of the troubles of reality, and the dizzying emptiness beneath it.

Mind that "constructive" here is absolutely not synonymous with "optimistic". I take huge issue with the entire triad of (colloquial) optimism-pessimism-realism, all for the same fundamental reason: they're ideologies of complacency and passivity. Optimism goes "there is no problem, so there's no need to take action to solve it" -- these days, it feels very downstream of CBT, with this idea that problems can be eliminated by simply vehemently denying their existence, reducing them to nothing but so-called "cognitive distortions". Pessimism goes "the problem is insurmountable, so it's pointless to try to take action against it" -- essentially the opposite reasoning, but with the exact same outcome. Realism, meanwhile, is basically just a mix of the previous two positions based on whichever one/combination best justifies passivity in a particular situation. How often are calls to "be realistic" anything other than attempted shutdowns of someone trying to act?

In the context of the emptiness problem, optimism says "life isn't hollow, reality isn't false, you're just mentally ill!", pessimism says "life is hollow, reality is false, and there's nothing we can possibly do about it: all that's left is to despair", and realism says "whichever one it is, that's not going to change the fact that you just need to get on with your life instead of fighting against reality itself". None of these positions are remotely satisfactory.

I've become a dedicated unrealist: prioritising action above all else, including -- and especially -- "reality" itself. My previously discussed abandonment of smartphones and social media has been one major project in unrealism. Naturally, the most common objections to it are "realism"-based: you just can't get by without smartphones/social media, it's not possible, it just can't be done, it's unrealistic... Well, evidently, it is possible. Unrealism is to spit in the face of "reality", to strip off its illusory presentation as absolutely true and fixed, exposing its actual nature as fluid, glorified superstition -- or, rather, hyperstition. It became "impossible" to live without smartphones/SM once enough people decided that it was impossible to live without them. You can observe this phenomenon of hyperstitional reality-construction in real time now with the rise of genAI: the spread of beliefs along the lines of "genAI is the future, I have to get on board with it whether I like it or not because everyone's going to be using it, I'll get left behind if I don't" is precisely the reason that said beliefs are on track to becoming a reality. Unrealism recognises this utter absurdity inherent to "realism" -- that it works to bring about unfavourable outcomes -- and therefore rejects it.

Back onto the emptiness problem -- the unrealist approach to this is what "black space" is all about. Action above all else: staring into the void, but facing it constructively. Unrealism is the radically artistic view of the world: that literally all creation is art, from the highest of archetypical "fine art" to the tiniest of ephemera -- from "crafts" to language to even something as infinitesimal as the way you pour your cereal for breakfast*. That, if anything could be said to be the "meaning" of life, it's art -- creation. Or, more accurately, that creation comes before even objectivity. The overwhelming emptiness and meaningless beneath the veil of reality is merely a well of endless creative possibilities.

*Languages are literally giant collective creative projects shared among billions of people all around the world across the entirety of human history. How people can not see languages as art in themselves, and uniquely awe-inspiring forms of art at that, is beyond me. On examining beliefs about what art is, it becomes incredibly obvious that they're all completely arbitrary. For instance, I've heard that video games don't count as art, because they are too interactive and open. What? Are we really going to pretend as if this isn't just a hollow ad hoc justification for the specific purpose of excluding video games from categorisation as "art", rather than actual independent belief in these statements in and of themselves? Or do performance art pieces hinging on spectator interaction not count, either?

Lundi 2 Sable 153

Blogging

As a child I almost exclusively wrote by hand, and more recently my technophobia led me to avoid digital formats for a while, but now I've actually come to really appreciate the blog format. Handwriting is very fixed and static: only minimal edits are able to be made, so once you've written a piece that's pretty much it, the process is over -- if you want to make major changes, you have to create a whole new piece. I enjoy the extreme flexibility of this blog format: a piece is never finished, you can always go back and change it in whatever way you'd like.

I'm very new to being alive, and therefore very unexperienced in absolutely everything, so writing something always starts off very experimentally. So, naturally, whenever I reread something on its first version (or second or third or...), it's riddled with logical holes. It's helpful to be able to focus in on correcting those holes specifically, rather than having to rehaul the entire thing. Basically, the format itself reflects the fluid, continuous process of learning.

Ultimately, the ethos of the blog is exploration. I don't believe in having beliefs: my posts are much more exercises and experiments than some fixed, static declaration of "what I believe". Really, all writing is just experimentation on different levels, and I'm just constantly practising to try to reach higher. Perpetually writing is just as important as perpetually reading, and neither are ever finished.